It’s a brave new world for Christopher Nolan, who recently ended his historic relationship with Warner Bros. Once a legendary alliance that gave us the likes of masterpieces from The Dark Knight to The Prestige to Inception, among others, a stubborn dispute over Warner Bros.’ day-and-date COVID-19 streaming plan has driven Nolan to the open arms of Universal for his latest project; Another adaptation of WWII-era history, Oppenheimer.

Following 2017’s Dunkirk, Oppenheimer brings Nolan back to a period of time that he appears to be particularly fascinated with. It also continues the rising trend of blockbuster Summer biopics that Elvis, ironically a Warner Bros. production, started flirting with last year. Of course, this detail has been firmly overshadowed by the online phenomenon of “Barbenheimer”, resulting from Universal making the bold choice to release Oppenheimer on the same day that Nolan’s old studio buddy, Warner Bros. also premiered their new blockbuster, Barbie to the general public.

Barbenheimer is a strangely perfect encapsulation of two equally appealing extremes of cinema, with Barbie thriving as pink, sugary escapism, while Oppenheimer delivers a masterful, yet overwhelming portrayal of real-life history. Funny enough, both Oppenheimer and Barbie, now inextricably linked due to their unorthodox release strategy, also deal with themes of existential crisis and disillusionment. Perhaps they are a strangely perfect pairing in their own unique way.

In this review however, we’re strictly talking about Oppenheimer, which may just stand as another of Nolan’s top masterpieces. It’s a dizzying, complex and often deliberately confusing look at a time when history was changed forever, while still leaning into Nolan’s panache for designing his movies like cinematic puzzle boxes. Sure, Oppenheimer’s staggering three-plus-hour length can make an already challenging movie even more challenging to take in all at once, but even if you’re best off skipping the large drink for this one, this ambitious biopic nonetheless stands as a master class in historical cinema that demands to be seen on the big screen, balancing its existential dread with a thoroughly riveting perspective on the cause and effect of human progress.

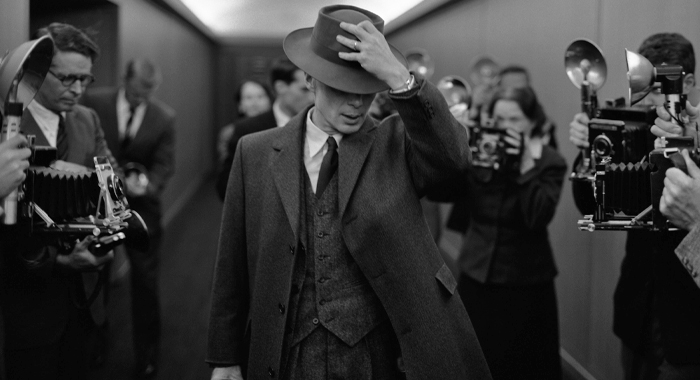

Cillian Murphy, one of Nolan’s longest standing and most celebrated collaborators, is thrust into the center of a biopic that’s absolutely packed with noteworthy names, both throughout the cast and throughout historical record. Murphy of course portrays the eponymous mastermind behind the atomic bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, Japan in 1945, thus giving birth to a new age of nuclear deterrence, and indirectly, the Cold War. If you’re familiar with the man at all, it’s probably due to his famous response to the horror behind his creation; “I am become death, destroyer of worlds”, a passage taken from Hindu scripture.

Far from a mere merchant of death however, Oppenheimer initially portrays Murphy’s lead as a lost genius with good intentions, but also antisocial, and sometimes even hostile tendencies during his early academic career in the 1920’s. Yet despite his well-known historic influence, viewers will find that across a slew of perspectives that jump back and forth through time, between the 1920’s to the 1960’s, it’s easy to almost feel like Murphy’s Oppenheimer isn’t even truly in control of events around him. Indeed, he seemingly becomes a pawn of destiny itself while trying to find a way to bring the study of quantum physics to a wider audience in America, something that also gets him tangled up in the Communist Party.

“Did Oppenheimer save the world, or condemn it at a later time? Even Murphy’s eponymous lead doesn’t know, and that confusion is both fascinating and frightening.”

If that already feels like a lot of complicated events, trust me, I’m barely scratching the surface of what Oppenheimer portrays. J. Robert Oppenheimer is an enormously complex personality to try and bring to the screen, but Murphy manages to capture both the best and worst sides of one of the most controversial figures of the 20th Century. It calls to mind that the road to hell is paved with good intentions, as Oppenheimer, a Jewish man, initially seems excited at the frontiers of atomic science, particularly as a way to loosen Hitler’s murderous grip on his people during the Holocaust. Even before the first formal bomb test however, the incessant torment of, “The new world” continues to plague Oppenheimer, who eventually becomes a staunch opponent of further nuclear development, ultimately and tragically failing to prevent the rise of the Cold War that would follow WWII.

What makes Oppenheimer so effortlessly riveting throughout even its enormous runtime isn’t necessarily these larger-than-life events, which are almost background noise in the end. We don’t actually see the scars and panic wrought by the atomic bombs, for example; They’re merely discussed, and acknowledged by public reactions. This would normally be a questionable choice for a filmmaker, as cinema is a medium about showing, not telling. Ingeniously however, through keeping the focus on discourse over destruction, Nolan keeps his latest masterpiece in check, and on task.

Appropriately then, a big part of why Murphy’s lead performance is so effective is because it doesn’t give us definitive answers about who Oppenheimer is in the end. Like all mature and rewarding biopics, Oppenheimer presents us with the information at hand, and trusts us to judge for ourselves. Is this man a servile mass murderer that was exploited by the American government? Is he a misunderstood genius that did what he had to do to prevent further destruction? Most simply, did Oppenheimer save the world, or condemn it at a later time? Even Murphy’s eponymous lead doesn’t know, and that confusion is both fascinating and frightening, ultimately delivering an enrapturing lead performance that will no doubt mean many things to many viewers.

There are far too many personalities in play throughout Oppenheimer’s cast to adequately break down in just one review. Thus, I’ll try to focus on the biggest names in the movie, which include a mix of new and returning Nolan collaborators, albeit mostly new faces. Some have large roles, some have small roles, but everyone feels in some way pivotal within the quest to try and understand how much or how little J. Robert Oppenheimer ultimately contributed to the destructive project that history would go on to permanently connect him with.

For the most part, Nolan’s returning performers, aside from Cillian Murphy in the lead role, are surprisingly kept to smaller appearances. Gary Oldman, for example, only appears in one key scene as a blink-and-you-miss it President Truman. David Dastmalchian meanwhile, returning from his brief appearance in The Dark Knight, portrays William Borden, a personality that appears rarely, but otherwise serves as a crucial voice in the allied development of further nuclear weapons, ultimately becoming the blunt instrument for Robert Downey Jr.’s nuke-pushing antagonist, Lewis Strauss. Finally, Kenneth Branagh returns after portraying the primary antagonist of Nolan’s previous 2020 effort, Tenet, this time portraying noted physicist, Niels Bohr in Oppenheimer, a man who would unwittingly open some very necessary doors for Oppenheimer’s development of the atomic bomb.

Oppenheimer’s female leads also serve as excellent foils in the further development of Oppenheimer’s portrayal. The larger of these is Emily Blunt as Oppenheimer’s drunk, surly wife, Kitty, a former Communist sympathizer and divorcee who also ends up tied to Oppenheimer through accidental circumstances, namely an unexpected affair, and an unplanned pregnancy. Even the Oppenheimer family marriage is another fickle whim of fate, a destructive, yet astonishingly solid mechanism that holds together two people that outwardly have no business building a family together, but indeed, it never seemed up to them in the end. This is in contrast to who may have arguably been Oppenheimer’s true greatest love, Jean Tatlock, played by Florence Pugh, a mentally unstable psychiatrist and proud Communist, whose own tragic story ends up having far-reaching consequences for Oppenheimer’s future as the credited father of atomic weapons. Like Blunt’s, Pugh’s performance is grumpy and erratic, but still has enough moments of tenderness to prevent her from feeling like an overall shrew, thus creating a duo of love interests for Oppenheimer that are just as interpretive and complex as he is.

From there, you’ll see no shortage of recognizable actors in Oppenheimer’s supporting cast: Matt Damon, Rami Malek, Josh Hartnett, Benny Safdie, Casey Affleck, Jason Clarke, James D’Arcy, Dane DeHaan, Alden Ehrenreich, Jack Quaid, Josh Peck, Olivia Thirlby and James Remar, to name a few. They’re all directed sublimely, even if it can sometimes be tough to keep track of who’s who. Recognizing key roles like Oppenheimer, his family, and Strauss, eventually the main force working to bury and discredit Oppenheimer in a bid to gain an advantage in the coming arms race, isn’t too difficult. When you try to place everyone else however, Oppenheimer can become a bit of a task, especially if you’re not a history buff.

Like I said, everyone is directed sublimely, but if you’re not specifically expecting a three-hour epic among biopics, it’s inevitable that not everyone can leave a major impression. You won’t get the sense that anyone is unimportant, thankfully, but if anything, Nolan has done almost too good a job assembling a stellar supporting cast for Oppenheimer. Some of this overwhelming feel across the cast is no doubt intentional, especially as Oppenheimer presents its plot in a non-linear fashion, jumping back and forth in time practically at random, but it is, regardless, an overwhelming feel. In the end, this incredible attention to detail is probably impossible to fully appreciate on a first viewing, in true Nolan fashion. Even so, subsequent viewings will no doubt depend on one’s desire to consume existentially stirring, multi-faceted cinema, especially considering that Oppenheimer’s semi-bleak conclusion doesn’t exactly make it an uplifting spectacle to sit through.

Oppenheimer is built largely around debates, philosophy and questions around the limits of common good and decency. Lest we forget, it is a Christopher Nolan movie. Despite all its heavy emphasis on talking, arguing and musing however, Oppenheimer is noteworthy for its painstakingly refined direction, granting a true sense of blockbuster flavour to a movie that could have easily felt laboured and dry.

Nolan’s direction can be disorienting, and it rather pointedly catches audiences off-guard with its almost unhinged shifts between eldritch imagery of foreign dimensions and particles. It’s no doubt done in an effort to bring audiences more easily into the perspective of Oppenheimer himself, suddenly tormented by visions that he and the viewer can’t understand, alongside a well of emptiness that seems to grow bigger as the consequences of Oppenheimer’s work become more palpable.

In fact, that sense of emptiness punctuates an unusual rarity for Nolan movies; Oppenheimer’s sound design is strangely quiet and understated throughout much of its runtime. This stands in especially notable contrast to the overwhelmingly loud and brash Dunkirk, which was so borderline deafening that it risked Nolan, an infamously noise-obsessed filmmaker, almost plunging his mighty audio stylings into self-parody. Surprisingly, Nolan instead decides to go against his own familiar sound style throughout much of Oppenheimer, but it really ends up working brilliantly here.

“Despite all its heavy emphasis on talking, arguing and musing however, Oppenheimer is noteworthy for its painstakingly refined direction, granting a true sense of blockbuster spectacle to a movie that could have easily felt laboured and dry.”

Sure, there are definitely moments where the delayed boom of a test bomb will blast over audiences with deceptive timing, almost threatening to blow out their eardrums in an IMAX viewing especially. Through exercising a shocking amount of auditory restraint however, Nolan picks his moments to flex the sound mixing best in Oppenheimer. Beyond the expected bomb blasts, there are also key scenes where incoherent crowd noise and rituals will suddenly pound on the audience’s senses, further plunging them into a sensory hysteria as Oppenheimer keeps losing more and more control of his own project. Through visuals and sound alike, Nolan has enabled Oppenheimer’s thoughts and perspective to almost take life in front of the audience, making Oppenheimer the rare biopic that truly does demand a theatrical viewing experience.

Even Nolan’s careful use of colour keeps scenes fresh and engaging, while also helping to differentiate between key time periods. Completely monochromatic scenes that take place in the lead up to the arms race, for example, nicely illustrate a sense of alien naivete that comes with the new threat that the world now faces. Suddenly, what was once recognizable is now very cold and ominous. Likewise, Nolan playing with colour in other scenes helps influence the mood between promising, to melancholic, and even to terrifying. The most impressive element of this highly detailed direction is that it’s all done without shock value and obnoxious gimmicks to boot. Instead, Nolan simply lets his biopic breathe in its own story, trusting the material to carry the production values, and in so doing, creating a master stroke of real-life storytelling that doesn’t need cheap tricks to feel powerful and interesting.

Oppenheimer can leave you feeling drained, due to its sheer scope and complexity, along with its heavy themes of existential dread. That being said, it also stands as easily one of the most impressive movies of 2023, as well as one of the defining masterpieces of Christopher Nolan’s career, right up there with The Dark Knight.

This epic biopic provides an examination of its subject with equal parts interpretation and enlightenment, simultaneously feeling both riveting and effectively inconclusive. We talk a lot about changing the world these days, but Oppenheimer reminds us that, regardless of intention, major milestones of human progress can create as many new problems as they solve old ones. Rather than provide a definitive solution to this age-old riddle as well, Oppenheimer instead encourages us to ask ourselves where the line is between necessary progress, and unchecked destruction. After all, as this movie itself states, destruction is an act of creation in its own way.

The fact that Oppenheimer can’t definitively assure us when it comes to where the fallout (pun not intended) of Oppenheimer’s atomic bomb truly stops can indeed feel quite bleak, and yet somehow, this movie also doesn’t forget to observe that progress is not something to be feared as much as respected. In true Nolan fashion, you’ll be left with more questions than answers by the end credits, but much like the world-changing career of its subject, Oppenheimer will also have you in awe at the sight of what a true genius can achieve when an injured world finally gets out of their way.